This year’s long post about trains.

Weighed down with 5 days-worth of food I never eat at home (cups-of-soup, pot noodles, instant coffee) I am bright and early for the 13:50 Moscow to Chitra train #70, making about 100 stops over the 5 day trip to Irkutsk in far eastern Siberia. Of the many trains on the Transsiberian route, foreigners prefer the more lavish #3 and #4, but I expect the older Chitra to be more solid, plus it arrives in Irkutsk at the more godly hour of 10:00 am on Friday, rather than the middle of the night.

It is not quite clear why Lonely Planet advises getting to the station 2 hours in advance in order to identify the train.

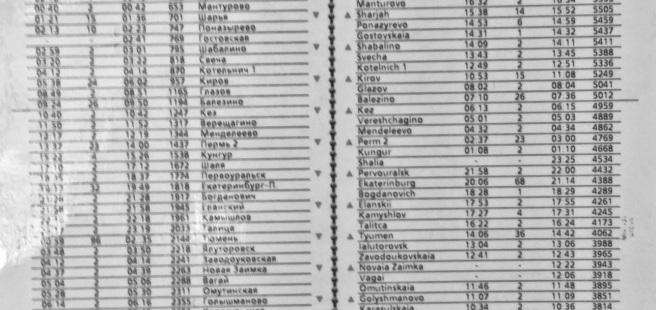

A mere smattering of those 100 stops. The engine is changed every night.

Train 70 Moscow to Chita

I easily identify carriage 8 (it is between 9 and 7, unlike the UK trains) and then my compartment midway between the samovar and the toilets (bunk #13).

Chill Lonely Planet, this isn’t rocket science.

But wait! In contrast to the undertaking by Russian Railways that ladies will be put together, bunks 11, 12 and 14 are already occupied by gents, at least one of whom has evidently never seen the inside of a shower he trusts. I am outraged and corner the prodenitsa (aide for our carriage) who is assiduously mopping the toilet floor. “It was my understanding” google translate begins in a passive aggressive tour de force “that were it possible for ladies to be together in a compartment, it would be so. And it does in fact appear to be possible”. Indeed it does. The carriage is not full and other ladies are in compartments alone. The prodenitsa observes me narrowly. She has seen it all before. She hopes that these statements are not an attempt to impugn the honor of these fine Russian gentlemen. Regrettably, at this point no changes can be made, so she also hopes that nonetheless a comfortable and satisfying journey can be achieved to (her eyes narrow even more) Irkutsk. She is not swayed by my final desperate plea that they are smelly.

At this point a choice must be made. The trip from Moscow to Irkutsk in eastern Siberia will take 3 full days and two half days on either end (4 nights). I have been waiting for it for literally 50 years. There won’t be a do-over (even if I repeat it there will never be another first time). So I need to get over it and get on with it.

Dimitry, Pyotor and even potentially Vasily-the-unshowered turn out to be sweethearts, just as the prodenitsa has optimistically advertised.

D is a millennial whose single passion is helicopters. Fortunately he is training to be a helicopter pilot. By the end of day 1 he has shown me every single picture on his computer, all of which are of helicopters, plus some videos of him as a pilot. The linguistic effort exhausts him and he sleeps in until 10 on day 2. Fortunately also, his phone is dead, so he has to spend the trip studying for his exams rather than watching videos.

P is a quintessential dad whose kids are set to surpass his wildest dreams (one is an architect and the other at Moscow University). He works for Gazprom but not in the Moscow office (this is significant to the other 2 who nod sagely). I presume that if he was an oligarch he would fly to Irkutsk, which takes about 3 hours. (Update: we later learn he makes this same trip from Kalliningrad on the Baltic to Siberia once a year to visit his mother. Once he disembarks at Irkutsk he has a further 6 hour train trip north followed by a 3 hour bus ride into the taiga. All in all the round trip will take a month. He does it by train because he is afraid to fly).

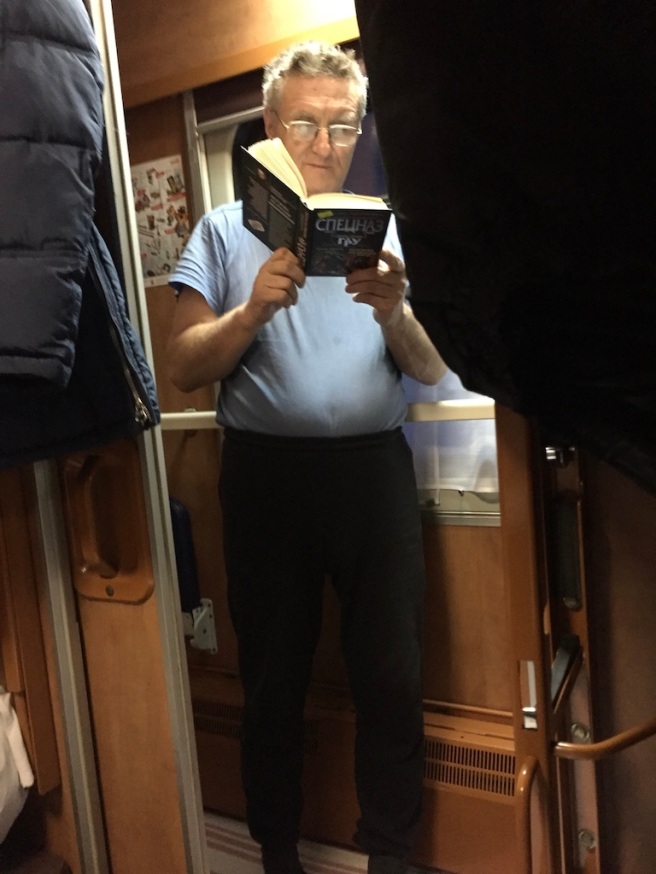

Dmitry fueling up for another bout of helicopter splaining. Pyotor taking advantage of the minute and a half of cell phone service available for the next 100 miles.

V – the – unshowered (and also it will turn out, the snorer) is more of an enigma. He has the bunk above mine and therefore during the day should share mine as a seat. But V doesn’t like to sit next to me or look me in the eye and so he alternates between squeezing in with the other 2 on the opposite side (which subtly exasperates them) or standing in the corridor. At dinner (pot noodles for me, pasta for P, and for D two competing 3 course meals from his divorced parents) D and V get into an intense discussion later described to me as about ‘political history’ during which D is too well-mannered to roll his eyes. After dinner V ascends to his bunk and falls asleep at 8pm. (Update: V has warmed up this morning and unbidden scurries through the carriage to identify the cleanest toilet for me. They are both clean. The prodenitsa’s obsession with mopping and dusting far outweigh her intransigence with seat assignments).

Vasily prefers to stand in the corridor rather than sit next to me.

Within a few hours the three of us (P, D and me) have settled on an effective way to get the most out of our combined 300 word vocabulary (there is usually no cell service or internet en route so GT is sidelined). I ask a question and then rephrase it a couple of times. They confer among themselves for a consensus answer which P delivers (D has more words but often gets hold of the wrong end of the stick). If it is a question they are particularly interested in (about 1 in 5) someone will bring out a napkin for a more thorough written response. We adopt a calming rhythm of ignoring each other until meal times and settle in for a nice discussion (and D’s pictures) in the evening. By the end of day 1 we have covered the cost of health care, universities and income tax and admired D’s college transcripts. I am hopeful we will move onto politics tonight since they have shown surreptitious interest in my book on Stalin. After the first night all the compartments are filled up, but few seem as convivial as ours. Moreover, in contrast to the hysterical admonitions of Lonely Planet, we leave our electronics lying around and not only do we not lock ourselves in at night, we leave the compartment door ajar, which is just as well since it is hotter than hell and everyone is in T shirts or pajamas.

Bunk #13 all set up for the night. The pillowcase from home is my best hack: I can stuff my parka inside thereby defending myself from the Russian Railways ‘pillow’.

The built up environs of Moscow drop off after about 3 hours and now, nearly 24 hours later, all we see through the dense gusting snow are isolated villages burrowing into the drifts. The village houses are mostly well kept but only some have smoke coming from their chimneys. Between them the larch forest is still interspersed with fields and from time to time we see ski tracks and even occasionally, resolute skiers. About every hour there is a small, quiet town. It is bliss.

During day 2 we pass over the Urals (rather disappointing as mountains – they achieved their full potential several millennia ago). They too are dotted with cozy villages nestled into the snow. Notably fewer of them are inhabited.

Not how I’d imagined the Urals (before it really started snowing).

On day 3 we cross the wasteland that is the desolate marsh of Western Siberia. Within the bog many trees are stunted and dead, like a first world war battle site and it appears fully devoid of humans or their habitation: There are no roads and we pass only two villages all day, only a few railroad workers’ cottages, glimpsed through the blizzard, huddle dispiritedly alongside the train tracks.

A rare sign of life in Western Siberia.

When I tell D & P this intense snowstorm is being called ‘the beast from the east’ V, from his top bunk, observes that it is in fact ‘the beast from the west’. My rush to impute nationalist motives is corrected by D, ever the didact, who points out the actual direction of the wind.

The blizzard outside may be raging but carriage 8 has settled into a bustling rhythm that demands careful attention. First of all is the matter of time. Carriage 8 like all Russian trains en route adheres to Moscow time, which is a full 5 hours different from where we will end up in the east, promoting an existentialist dilemma where at any given moment the clock at the end of the carriage bears no relationship to either our phones or laptops (further complicated by the fact that cell phone service can only optimistically be called intermittent and we have had internet only once in 3 days) or, more significantly, our biological clocks. Not only do we sleep in until ungodly hours but the little elf who runs the restaurant can deliver meals he calls ‘dinner’ at times no sane person would want to eat. (We each get one free meal. D and V, who are getting off midway in Omsk had their ‘dinner’ at what they thought was 3pm on day 2. P, the Transsiberian expert, who is getting off with me at Irkutsk has decreed we will have ours on day 4 when the arrival of ‘dinner’ may coincide with our biological breakfast, or something).

Only the blazing sunlight provides a clue that in fact it might not be 4:49 in the morning. The heat in the carriage has been turned down for the night.

We stop about three times a day for long enough to buy food from the babushkas who man dank kiosks or more disconcertingly flash their merchandise from where it is pinned inside their coats. Hard boiled eggs are 25 cents, train-proof bread that never tastes good or but never goes bad 50 cents, and questionable salami a dollar.

If we want to eat tomorrow we must brave the kiosks tonight.

.On one occasion I buy some smoked fish. Inside, enveloped in fetid heat, it starts to smell after only 10 minutes. They implore me to eat it quickly, but even so P is forced to spray the compartment with pungent deodorant in self-defense.

Making no friends with this evening’s menu choice.

The carriage is looked after by two prodenistas. It should be pointed out that their job is to look after Russian Railways hardware, not its passengers. To this end Nadzheda toils all morning (Moscow time), which means she turns up randomly by day and night, poking her vacuum between our feet and insisting we lean this way and that so she can polish behind our backs and clean the windows When we stop she scurries outside to chip the ice from the undercarriage. It has not escaped our notice that Nadzheda pays most loving attention to the bathroom nearest her little compartment, which is always sparkling clean and well supplied with toilet paper. Tamara works at night (Moscow time) when our opportunities to despoil Railway property are minimized, so she can concentrate on her specialties of paperwork and Sudoku. Three hours after carriage 8 has been cleaned to within an inch of its life a man with a clip board comes round to inquire after our satisfaction. Since the surveys must be accompanied by a Russian ID (supplied reluctantly by D and P) he is not interested in my opinion. Remarkably, their comments will be published on the Russian Railways website, as I discovered once accidentally. V on the top bunk keeps resolutely mum.

All hands on deck, or rather under the deck.

Carriage 8 before Nadzheda has vaccumed the corridor and straightened the runner.

According to Lonely Planet, Transsiberian trains #3 & #4 will provide a non-stop party experience, but in carriage 8 on the 1950’s Chitra express the subtle etiquette is much more decorous. Lower bunks get the window seat near the table, but when the others indicate an intention to eat by rustling in their food bags it is considered polite to shift out of the way and leave the compartment. It is not polite to comment on food, unless invited (exception – smoked fish as mentioned, and my pot noodles which invited discreet scorn but then an avalanche of invitations to salami and cheese). Cookies are left on the table for communal use and should be pressed on others whenever eye contact is made. Tea is drunk 8 times a day.

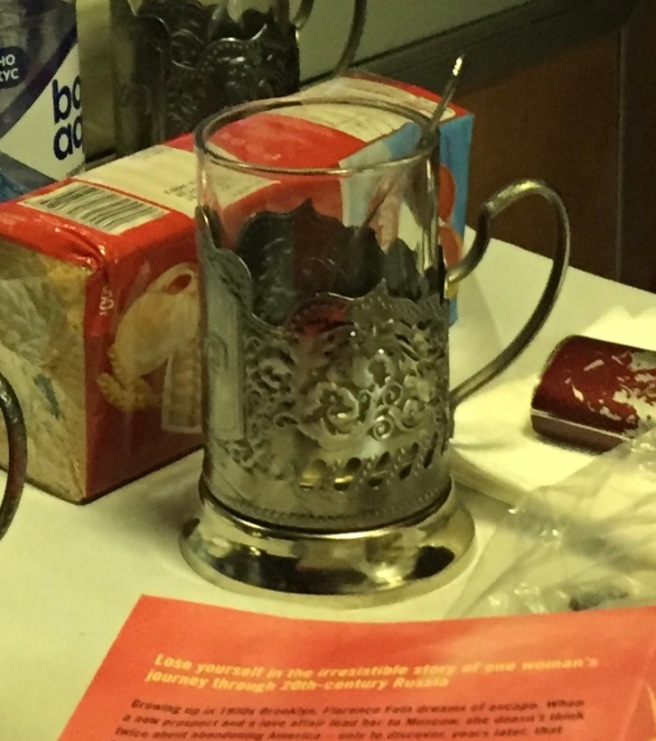

Russian railways help out with the tea drinking requirement by providing mugs.

And a samovar

D & V depart at Omsk on day 3 (V thaws completely and kisses my hand). Unfortunately this unexpected outpouring of emotion causes him to forget his passport unleashing a tsunami of bureacracy in the service of dropping it off at the next station (Ob, population 10, six hours away). V & D are replaced by a deaf woman and at midnight (actual time) a sulky millennial who is welded to his iphone. We accommodate and the conversations begin again.

I am reluctant to disembark. After all there are still three more days before Chita, not to mention Vladivostok.

I laughed a great deal reading this, Karina: the small things and acute observations about people and travelling companions are treated with such a good eye and with such humanity. I feel I am there.

Can’t wait for the next épisode. Our beasr, whether east or west has died down, at last.

X

Rhiannon

LikeLiked by 1 person

Karina – Your conversation with the waitress in Moscow was hilarious. I hope that you make it to Irkutsk without having to sit in silence. What an adventure! Keep the posts coming.

LikeLiked by 1 person